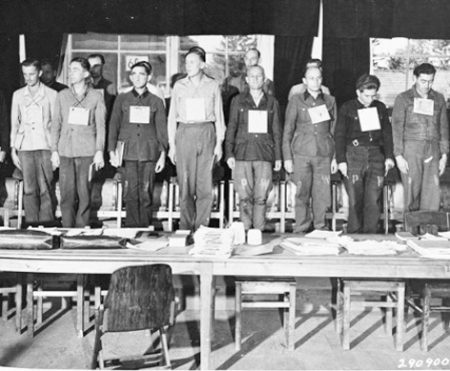

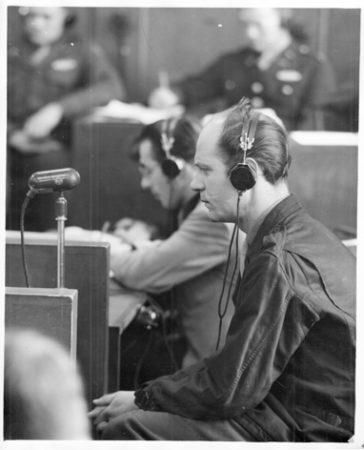

Just about everyone knows the story of the International Military Tribunal Trial held in Nuremberg, Germany between 20 November 1945 and 1 October 1946. Commonly known as the Main Nuremberg Trial, twenty-four senior Nazi party officials and military officers were indicted on one or more of the four charges: conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity (click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Enablers-Part One). Twenty-one defendants sat in the dock (Martin Bormann was tried in absentia, Alfred Krupp was too ill to attend, and Robert Ley committed suicide). Twelve men were sentenced to death, three were acquitted, and the remainder were given prison terms ranging from ten years to life imprisonment (click here to read the blog, Court Room 600).

By the time the main trial ended, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France had had enough of Nazi trials and future trials were carried out by the Americans and countries where Nazi atrocities had occurred. The twelve Nuremberg follow-up trials between October 1946 and April 1949 were held in Court Room 600, the same venue as the main trial. Defendants in the twelve trials included doctors, lawyers, industrialists, administrators, and members of the Einsatzgruppen, SS mobile killing units.

Subsequent post-war trials were held to establish accountability of the men and women who actively participated in the crimes and atrocities against their fellow human beings. The defendants were primarily lower-level party officials, officers, and soldiers. Among them were concentration camp guards and commandants, police officers, and collaborationist officials of occupied countries (click here to read the blog, Hitler’s Enablers -Part Two). The trials were conducted either in groups (e.g., Auschwitz, Belsen, Dachau, Sobibor, and Treblinka) or as single defendants (e.g., Rudolf Höss, Albert Kesselring, and Anton Dostler). Many of these trials were held in former concentration camps such as Dachau and Auschwitz.

It is here that Johnny’s story begins.

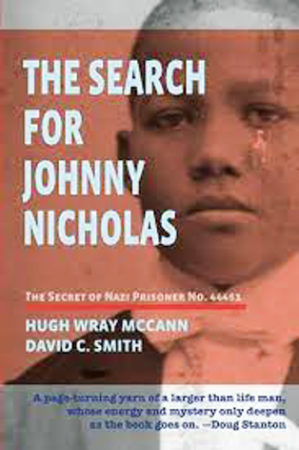

Understandably, there is very little information about Johnny Nicholas. The formative (and only) book devoted solely to Johnny is The Search for Johnny Nicholas by Hugh Wray McCann and David C. Smith. When I refer to “the authors” in this blog, I am speaking of Messrs. McCann and Smith. Mr. McCann first heard the story of Johnny in 1965 from a friend who had covered the 1947 Nordhausen War Crimes Trials. He and his journalist friend, Mr. Smith, decided to embark on a decades long journey to uncover the life story of a man who led a very interesting life before his untimely death at the age of twenty-six. I highly recommend you read this very interesting book but before starting Chapter One, I suggest you first read the Foreword (“How the Search Began”) and the Afterword (“The Search Within the Search”).

I will be the guest speaker for Bonjour Paris on 6 December 2023 for a Zoom presentation to their members and others. The topic will be “Walking History: In the Footsteps of Marie Antoinette” and I will take you on a walk along the exact route in Paris that the queen’s tumbrel took to the guillotine. I invite you to join us for the discussion and slide show.

Bonjour Paris (click here to visit the web-site) is a digital website dedicated to bringing its members current news, travel tips, culture, and historical articles on Paris. I have been a member for more than ten years and have found its content to be quite interesting, practical, and entertaining.

I will have a direct link to sign up for my presentation at a later date. There is no cost to Bonjour Paris members and €10,00 for non-members. The time of the live presentation on 6 December will be 11:30 AM, east coast time.

Did You Know?

Did you know that the term “genocide” was created in 1944 by the Polish-Jewish lawyer, Raphael Lemkin (1900−1959)? As a law student, Lemkin learned about the Armenian massacres and began what was to be a lifelong dedication to ensure international legal standards were established to hold perpetrators of war crimes accountable and brought to justice. In 1933, he published a pamphlet proposing the League of Nations create international laws pertaining to the mass murder of groups of people. While the publication was circulated, it was not formally discussed let alone accepted.

Eleven years later as the Nazi atrocities against the Jews and others became known, Lemkin came up with the word “genocide” from the Greek word, genos (family, clan, tribe, race, stock, kin) and the Latin word −cide (killing). He defined genocide as “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

Lemkin served on Robert Jackson’s legal team at the International Military Tribunal Trial at Nuremberg. The term “genocide” was used during the trial to describe the fate of the Jews and others under the Nazis. At the time, there was no international law covering genocide as a crime. However, in 1948, the United Nations established genocide as a crime under international law.

It’s interesting that if there were no international laws concerning the mass murder of groups of people until 1948, how were the Allies able to accuse and convict Nazis of “crimes against humanity”? Just a thought from someone who never contemplated or desired to be a lawyer.

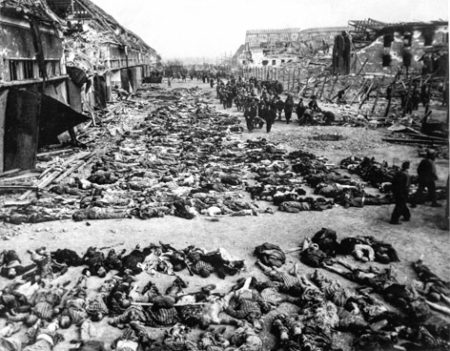

The Nordhausen War Crimes Trial

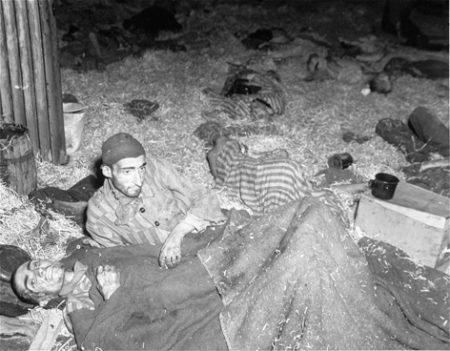

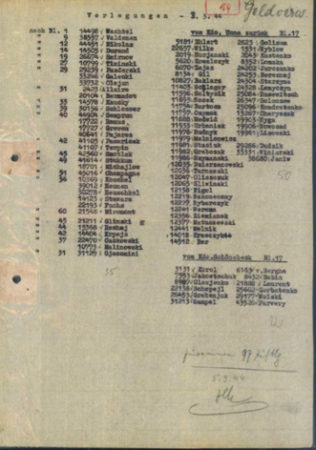

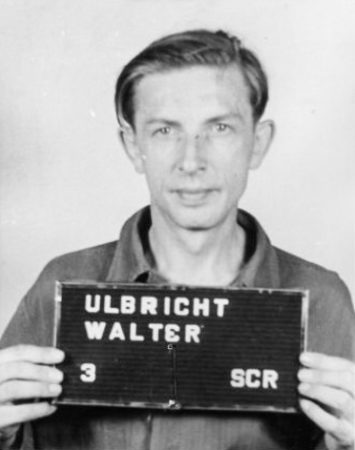

The Nordhausen War Crimes Trial, or “Dora Trial” was held between 7 August and 30 December 1947 at the site of the former KZ Dachau concentration camp. Nineteen men were accused of war crimes including intentionally participating in abuses and killings of prisoners of war and non-German civilians in KZ Mittelbau (“Dora”), its subcamps (including Nordhausen), and the nearby Mittelwerk armaments factory. Originally a subcamp of KZ Buchenwald, Dora became independent in October 1944 and continued to supply prisoners as forced labor to construct the underground production facilities used to build long-range missiles and other experimental weapons. (Dora prisoners were also used in the granite quarries, construction projects, ammonia works, and other weapons production.) In the tunnels, the prisoners endured horrible conditions including being deprived of daylight and fresh air. Prisoners too weak to work were sent to KZ Auschwitz II-Birkenau or KZ Mauthausen to be murdered. About a third of Dora’s 60,000 prisoners died from starvation, exposure, disease, abuse, and executions. In early April 1945, more than 36,000 prisoners were evacuated from Dora and sent on death marches to KZ Bergen-Belson, KZ Sachsenhausen, and KZ Neuengamme. A week later, Dora, Nordhausen, and Mittelwerk were liberated by the Americans on 11 April 1945, but very few of the remaining prisoners were still alive.

The Gardelegen Massacre

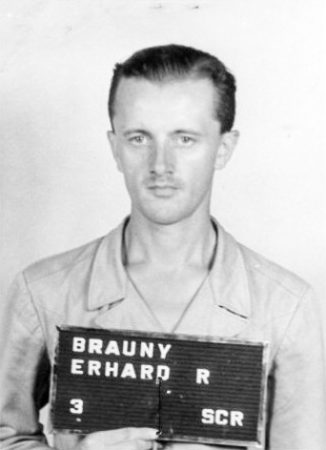

About the same time as the Dora prisoner evacuation, four thousand inmates from various subcamps (including Rottleberode) arrived in freight rail cars in the town of Gardelegen on their way to certain death in other camps. Outnumbered by the prisoners, the SS guards recruited locals to guard the Dora survivors and on 13 April, more than one thousand of the sick and weak were taken out of town to a large barn and forced inside. On the orders of the commander, SS-Hauptscharführer Erhard Brauny (1913−1950), the barn was set on fire and those who tried to escape were shot. Less than a dozen survived. The 102nd Infantry Division entered Gardelegen on 14 April and the next day discovered the smoldering barn and the remains of the massacred victims. Brauny was tried in 1947, convicted, and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died from cancer while in prison.

Find Johnny Nicholas!

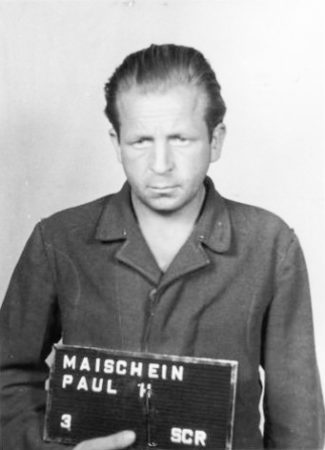

U.S. Army Lt. Col. William Berman was the chief prosecutor in the Nordhausen War Crimes Trials. He and his staff interrogated many former Dora inmates whom they would eventually call as witnesses. What they often heard during the interviews was a common name: Johnny Nicholas. They talked about a physically large Black American inmate nicknamed “Dr. Johnny” who was described as courageous, positive in attitude, and someone who passionately cared for Dora’s sick prisoners at the risk of his own life.

Col. Berman soon became convinced Johnny Nicholas could be his star witness against the defendants. He put out the order to find this Johnny Nicholas. Berman gave the assignment to William J. Aalmans, a well-respected Dutch investigator working for the 7708th War Crimes Group and responsible for interrogating both former Dora prisoners and the defendants. Aalmans looked for Johnny in every conceivable place. One search led Aalmans to the Gardelegen barn where a burned corpse was identified by former inmates as Dr. Johnny. They were mistaken but as far as Berman was concerned, the search for Johnny Nicholas was over at that point.

Fortunately, a young soldier and public information official, Cpl. David Matthews wrote a six-page account after the trial about Johnny’s activities. Matthews went on to become an attorney and the document sat in his old army duffle bag for eighteen years until one of the authors had dinner with him and learned about Johnny Nicholas.

Let’s Meet Jean Nicolas

Jean Marcel Nicolas (1918−1945) was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, a poor country that had been occupied by the United States Marines since 1915. He was the youngest of Hilderic and Lucie Nicolas’s three children (sister, Carmen and brother, Vildebart). His parents were French citizens, and the family was financially secure. Hilderic was Secretary at the British Embassy and enjoyed access to the upper echelons of government (i.e., the ruling class) and business (principally, the wealthy landowners). Jean grew up in relative wealth and experienced encounters with beautiful women, handsome men, and men in uniform that would shape his future demeanor and personality.

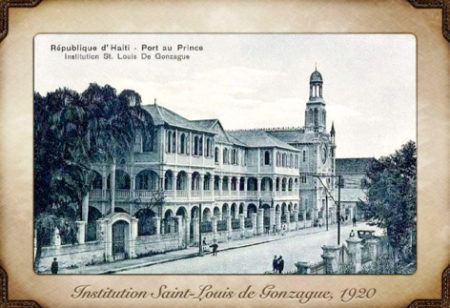

Jean attended the Institute of Saint-Louis de Gonzague, a private French Catholic school. He learned to speak fluent French as well as Creole and English (from the U.S. Marines whom he adored). In 1928, Hilderic sent his youngest son to France to attend Lycée Aristide Briand in Saint-Nazaire. (Vildebart was also a student there.) Jean was unhappy and his temper began to get the better of him when he came into conflict with fellow students who looked down on him. Although he felt more French than Haitian, Jean was referred in a derogatory manner by the other students as a Black “French colonial” or “Black savage.” Despite his success in academics, Jean and his brother withdrew from the lycée, and their parents sent them to College de Garçon, twenty miles from Nice, where the Mediterranean climate suited them. Although Jean was much happier, his brother’s health was suffering and after only one term, Hilderic brought his sons home.

The boys were enrolled in the Harry Tippenhauer Academy, a private school with a reputation for high academics and strict discipline. In 1972, the authors interviewed Harry Tippenhauer, an engineering professor at the University of Haiti and headmaster at the academy. Tippenhauer talked about Jean’s strengths in the areas of math, science, and foreign languages. Jean’s superior intelligence and an ability to quickly grasp just about anything meant he didn’t have to expend a lot of energy in studying. Jean was also stubborn and once he made his mind up, there was no changing his direction. His mother described her son to the authors as someone with a lot of tenacity. But above all, Tippenhauer noted, “He would help anyone in the class and completely forget himself. He was a special boy; warm and affectionate. If there was a friend who was in danger, he would give his life, and you couldn’t stop him from doing it.”

At the age of sixteen, Jean took up boxing. He did well in the ring and well-heeled daughters of the wealthy and powerful quickly befriended the six-foot muscular young man. Soon, he was attracted to the local brothels which were frequented by the marines. Jean got into a “boudoir” fight with three marines and ended up on the Marine Corps “Most Wanted” list. The decision was made that Haiti was too small for Jean and he would need to leave at some point.

An Ultimatum

In 1934, President Roosevelt declared the marines would be removed. While the American presence in Haiti resulted in many improvements for the small country, the marines caused resentment and problems. Despite his fight, Jean was heavily influenced by the Americans. Two years later, the eighteen-year-old got into serious trouble with the Port-au-Prince police and his uncle rescued him from receiving a serious beating and returned Jean to his parents. However, Uncle Fortune delivered an ultimatum to the teenager: Jean had to leave Haiti and Fortune would pay for his transportation. Otherwise, he wouldn’t rescue his nephew again. Jean took a while to consider the “offer” but in 1937 after Hilderic died, Jean enlisted in the French navy. A year later, Jean was dismissed due to an injury, and he ultimately settled in Paris.

Paris, Name Change, the Resistance, and Arrest

By the time the Germans marched into Paris in June 1940, Jean had changed his name to Johnny Nicholas and was passing himself off as an American citizen and a downed Allied pilot in hiding. Johnny was also involved with the local resistance. He was very popular with the women and went through numerous girlfriends. His final girlfriend was Florence. She had been an aspiring actress until the Germans showed up and by 1942, she was working as a résistant in an escape line aiding downed Allied airmen (click here to read the blog, Escape Lines). Florence couldn’t quite figure out Johnny. There were a lot of inconsistencies in his stories, but she was attracted to the confident American who spoke fluent French without any accent. She even once thought he might be a German agent and infiltrator. For Johnny, he violated one of the basic resistance rules: he became romantically involved with a fellow résistant. It would be a lethal mistake.

Johnny spent several months sharing an apartment with a downed American B-17 pilot. During that time, he learned about the pilot’s squadron, aircraft, and life in the United States. Growing up in Haiti, Johnny picked up a fascination for American cinema and actors. He was known to accompany and befriend French actors while passing himself off as a film producer. One of his many girlfriends was the film star and former Miss Paris of 1930, Vivian Romance. Johnny spent a year in medical school but never finished. He opened a medical office specializing in gynecology with a fake diploma from Heidelberg University hanging on the wall.

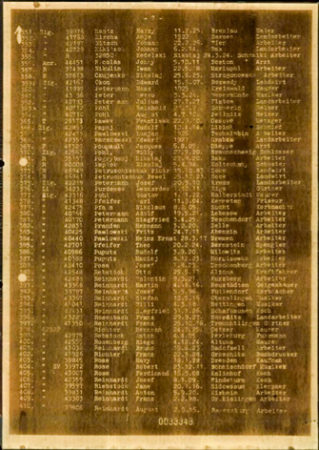

As Paris entered the fall 1943, Johnny told Florence she was his only girlfriend. When Florence found out Johnny lied to her, she denounced him to the Gestapo and early on the morning of 23 November, Johnny was arrested in his apartment on avenue de Lambelle. Handcuffed, Johnny was taken to Gestapo headquarters on rue des Saussaises and unbeknownst to him, the Germans classified Johnny as a Nacht und Nebel (NN) prisoner under Hitler’s 1941 lethal decree (click here to read the blog, Night and Fog). NN prisoners were not expected to survive and any reference to their existence was to be destroyed.

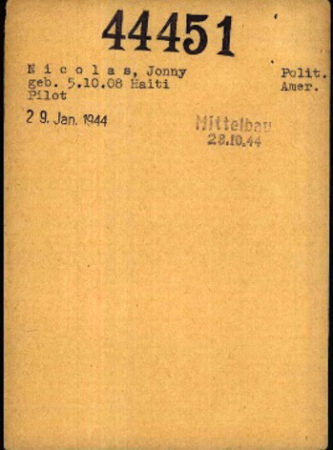

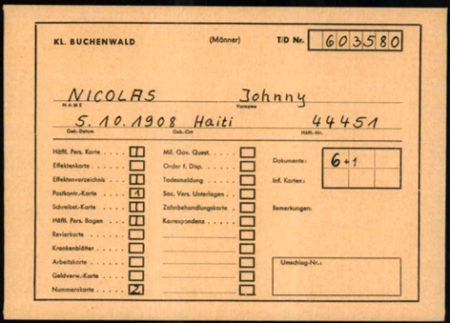

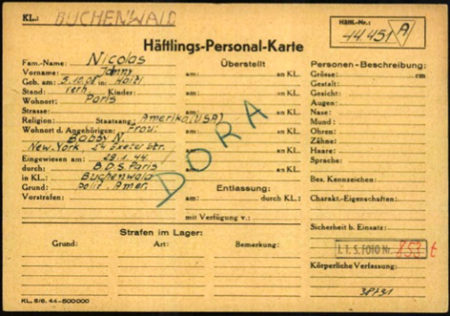

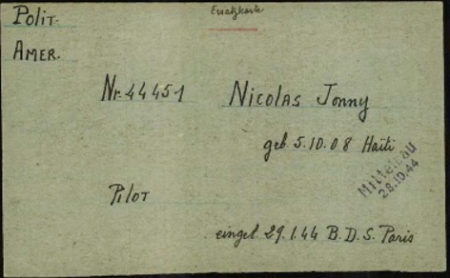

Nazi Prisoner NO 44451 – American, Allied Pilot, and Doctor

Despite all signs that Johnny could easily be an Allied spy (i.e., proficiency in various languages, a story that seemed too well rehearsed, and knowledge about the U-Boat pens at St. Nazaire), the Gestapo did not torture Johnny. He was transferred to Fresnes prison where he was a target for the sadistic guards because of his NN status and for being a Black man.

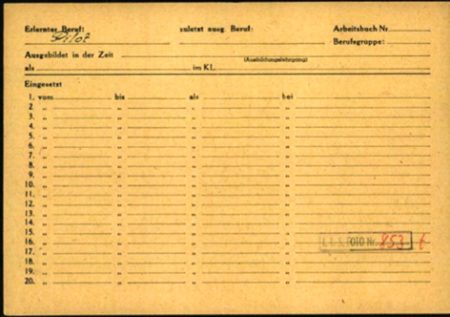

Shortly, Johnny was transported to Compiegne, the transit camp north of Paris. Johnny was held there until the end of January 1944 when he was trucked to Gare de l’Est in Paris and put into a boxcar with 119 other NN prisoners. Five days later on 29 January, Johnny arrived at KZ Buchenwald. Processed by camp kapos (prisoners assigned as “trustees,” or guards), Johnny was assigned prisoner no 44451 from Boston, U.S.A. and he wore the political prisoner red triangle stitched to his shirt. The large “A” in the center identified him as an American. His first assignment was in the rock quarry where it was “dig or die.” Johnny had never seen such brutality in his entire life.

Johnny quickly learned that to survive, he had to keep his mouth shut and keep a low profile. However, being black, physically imposing, and his past antics meant he had developed a reputation and couldn’t fade into the background. Quickly learning the politics of the camp, he ingratiated himself with the elite prisoners who got him assigned to the top of the rock quarry where the chances of survival increased. Johnny couldn’t imagine anywhere as dreadful as Buchenwald. He was wrong.

Dora

On 11 May 1944, Prisoner no 44451 was shipped to Dora. Johnny was assigned to heavy labor inside one of the tunnels with the purpose of enlarging the tunnel system to accommodate the manufacturing of weapons, notably the V-1 and V-2 rockets. The working conditions were horrible, and the fatality rate was quite high. Prisoners commonly contracted typhus and diphtheria. If you were dying, no one came to your aid. Johnny saw all of this and in September 1944, he managed to persuade the camp’s medical director, SS-Obersturmführer Karl Kahr (1914−2007), to “hire” him as a Prisoner-Doctor. Johnny was given a fresh uniform and assigned to administer to the inmates at sick call. Kahr’s new assistant treated wounds, set fractures, and prescribe medicines. Johnny quickly developed a reputation for being friendly, having a good humor, and above all, a competent doctor. He was always trying to lift the morale of the prisoners. After the war, many of the former inmates interviewed by Col. Berman fondly remembered “Dr. Johnny.” They should. Kahr and Johnny saved the lives of many inmates.

By the fall of 1944, the tunnels were completed, and the manufacturing of armaments had begun. In October, all construction ceased, and the prisoner population began to diminish.

Subcamp Rottleberode

Suddenly and unexpectedly, Johnny and others were ordered into a truck headed for Rottleberode, a smaller version of Dora and just as deadly. Kahr assigned Johnny to take charge of the subcamp’s infirmary. By Christmas 1944, everyone, including the Germans, knew Germany would lose the war and it was just a matter of time before the advancing Soviet army would be at the camp’s doorstep.

By mid-March 1945, the Soviets were 25-miles away. About forty thousand inmates remained at Dora and its subcamps when the evacuations began ⏤ Rottleberode was evacuated at dawn on 4 April.

Liberation

Johnny was one of seventeen hundred Rottleberode inmates called to final assembly. He was likely one of the prisoners marched toward Gardelegen. Survivors later placed him in the center of three columns of inmates. His column bypassed the town and so Johnny could not have been a massacre victim. Other unsubstantiated versions have surfaced but what is known for sure is that Johnny was suffering from tuberculosis and other ailments when he escaped from the march and ended up in Lübz (thirty-five miles south of KZ Ravensbrück) where he was found by an American tank unit on 3 May 1945.

On 26 June, Johnny was issued his repatriation card (no 1628080) by the French Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees. Riddled with tuberculosis and a bad leg wound, Johnny was admitted to the Hôpital Lariboisiere in Paris. He later demanded to be transferred to Hôpital Saint-Antoine where he passed away on 4 September 1945.

Johnny is buried in Paris at Pantin Cemetery. He rests between two nieces both of whom died in infancy.

Johnny’s Memoirs

During their research, the authors learned that while recuperating, Johnny had undergone debriefing by U.S. intelligence officers. This led him to write a detailed account of his activities during the war. This was confirmed by Vildebart but unfortunately, the manuscript has never been found. The authors’ book was originally published in Europe, and they had hoped a lead would materialize and Johnny’s manuscript would be found. Unfortunately, that did not happen and some of the missing pieces of Johnny’s story may never be discovered.

Was Johnny Nicholas a double agent as his uncle stated in a 1972 interview with the authors? Did Johnny work with the underground and black marketeers while in Paris? What was the extent of his resistance activities? Was Johnny an agent with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), British-led Special Operations Executive (SOE), or Gen. de Gaulles’s Bureau Centrale de Renseignement et d’Action (BCRA)? Did Johnny live in the United States for a while before his move to Paris? Was Johnny protected in Paris by a high-ranking German officer he knew in Haiti years earlier? These are some of the questions that will probably never be answered.

One thing we know is that despite his prisoner designation as NN, being Black, and his oversized personality, Johnny had a tremendous amount of luck, and he knew it. Otherwise, he would not have survived 17-months of harsh Nazi captivity.

Johnny Nicholas was a risk taker who loved life. For him, just merely living life was not enough. An extremely intelligent person, Johnny’s biggest attribute wasn’t his lust for life but the size of his heart.

Next Blog: “Operation Bernhard”

Correspondence and Commentary Policy

We welcome everyone to contact us either directly or through the individual blogs. Sandy and I review every piece of correspondence before it is approved to be published on the blog site. Our policy is to accept and publish comments that do not project hate, political, religious stances, or an attempt to solicit business (yeah, believe it or not, we do get that kind of stuff). Like many bloggers, we receive quite a bit of what is considered “Spam.” Those e-mails are immediately rejected without discussion.

Our blogs are written to inform our readers about history. We want to ensure discussions are kept within the boundary of historical facts and context without personal bias or prejudice.

We average about one e-mail every two days from our readers. We appreciate all communication because in many cases, it has led to friendships around the world.

★ Read and Learn More About Today’s Topic ★

Dodd, Christopher J. with Lary Bloom. Letters from Nuremberg. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007.

Fikes, Robert. Jean Marcel Nicholas (A.K.A. Johnny Nicholas, 1918−1945). BlackPast.org, September 17, 2017. Click here.

Gregor, Neil. Haunted City: Nuremberg and the Nazi Past. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Harris, Whitney R. Tyranny on Trial: The Trial of the Major War Criminals at the End of World War II at Nuremberg, Germany, 1945−1946. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1999.

Jacobsen, Annie. Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America. New York: Back Bay Books, 2014.

Lusane, Clarence. Hitler’s Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of European Blacks, Africans, and African Americans in the Nazi Era. New York: Routledge, 2003.

McCann, Hugh Wray and David C. Smith. The Search for Johnny Nicholas: The Secret of Nazi Prisoner No. 44451. Auburn Hills: Arbor Cove Press Michigan, 2011. First published in London: Sphere Books Limited, 1982.

Megargee, Geoffrey P. (Editor). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933−1945, Volume 1, Part B. Bloomington: Indiana University Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2009.

Purnell, Sonia. A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II. New York: Viking, 2019 (Page 42).

Täubrich, Hans-Christian (Project Manager). Memorium Nuremberg Trials: The Exhibition. Nuremberg: Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, 2012.

Taylor, Telford. The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir. New York: Knopf, 1992.

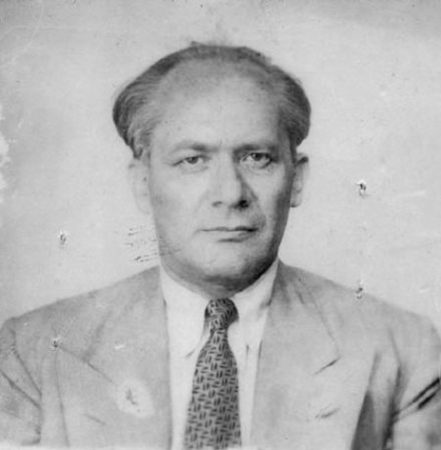

As previously mentioned, there is very little written about Johnny Nicholas. Messrs. McCann and Smith’s book was used as the basis for this blog. There are very few images of Johnny available and photographs from his early years are owned by his family. I managed to include several images of Johnny from his days in Paris. Unfortunately, I was not able to determine the owner of either photograph. Credit has been given to the web sites where I located the images.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

Sandy and I recently completed editing the second edition of Where Did They Put the Guillotine? Volume Two. (We were running out of books.) As always, thanks to Alex Pollock and everyone at Pollock Printing in Nashville for printing us a beautiful book.

We are preparing for our next cruise at the end of October. We’ll fly into Rome and catch a boat to float through the Suez Canal and then on to Dubai. Points in-between include stops in Greece and Jordan. We figured that going through the Panama Canal years ago meant we had to experience the Suez Canal. Same logic as cruising the Amazon and now, we had to do the Nile.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

Thanks to Patrick O’Bryon for opening a dialogue with us. Patrick is an author of historical fiction books and like me, his books are featured on Shepherd.com (see below). He recently mentioned his hotel experience in Bamberg, Germany. One evening, Patrick and his parents were subjected to a “rash of strange and disturbing sounds, hallucinations, and events.” The next morning, one of the waiters overheard them discussing the prior night’s paranormal activities. The waiter took Patrick to the side and divulged that the basement of the hotel had been used by the Gestapo as a torture chamber. I’ll bet Patrick works that story into one of his future books.

You can access Patrick’s books here. https://www.amazon.com/s?k=Patrick+O%27Bryon&crid=1JDY3ZC6JQWRJ&sprefix=patrick+o%27bryon%2Caps%2C123&ref=nb_sb_noss_1

I’d also like to thank Pat Vinycomb for introducing us to Johnny’s story. Her father, Stanley Booker, was deported to KZ Buchenwald to be executed (click here to read the blog, Last Train Out of Paris). She is doing quite a bit of research on the camp, and I suspect Pat ran into Johnny Nicholas on her journey down a rabbit hole.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Shepherd.com is like wandering the aisles of your favorite bookstore.

Do you enjoy reading? Do you have a hard time finding the right book in the genre you enjoy? Well, Ben at Shepherd.com has come up with an amazing way to find that book.

Shepherd highlights an author (like me) and one of their books. The author is required to review five books in the same genre. So, if a reader is interested say in cooking, they can drill down and find specific books about cooking that have been reviewed by authors in that category. Very simple.

If you like to read, I highly recommend you visit Shepherd.com. If you do, please let me know what you think and I will forward Ben any suggestions or comments you might have.

Click here to visit Shepherd’s website.

Click the books to visit Stew’s bookshelf.

Check out Stew’s new bookshelf on the French Revolution.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2023 Stew Ross

Hi Stew,

A fascinating Blog about Jonny Nicholas – thank you for publishing it. It is such an interesting story of survival and provides another perspective into the strength of character required by those prisoners who endured the horrors of Buchenwald and the other slave camps. The story behind a single name on a 79 year old Gestapo convoy list has come to life and his compassion towards his fellow prisoners acknowledged. A life remembered. Thank you

Hi Pat, Thanks for your comments. I only found out about Johnny’s story because of you. Keep those ideas coming! STEW

Stew

Greetings from Albuquerque!

I never tire of reading your blog. I saw the cover of about 4 or 5 books highlighted as best books on German occupation. I was surprised it did not include WHEN PARIS WENT DARK.

On another note, have you ever seen a book that covers the Gestapo filing system for keeping track of SOE or other agents.? The prison records included with your blog on Johnny were very interesting.

Cheers!

Patrick MORRISSEY

Hi Patrick; thanks for your kind comment regarding the blogs. I assume you’re referencing a list of books other than the lists I provide at the end of each blog. I’d be interested to know which books are highlighted. You’re right, I’m surprised that book wasn’t on the list. As far as a Gestapo filing system, the only one I’m aware of is the Tulard files. These were files kept on the Jews in Paris and used by the police in the infamous roundups. Today, the bulk of these files are kept in Paris at the Holocaust center. I’m sure the Gestapo kept files on the foreign agents but not sure if those even came close to the Tulard index files. Always good to hear from you. STEW